Political and electoral system of CR

Parliamentary Representative Democracy

The Czech political system is a parliamentary representative democracy, which allows citizens to elect representatives to make decisions on their behalf.

Three Branches of Power

Legislative branch (votes on laws)

=

Parliament

In Czechia:

The Chamber of Deputies (Sněmovna)

The Senate

Executive branch (implements laws)

=

Government

In Czechia:

The President

The Prime-Minister and the Cabinet

Judicial branch (evaluates laws)

=

the Courts

In Czechia:

The Constitutional Court

The Supreme Court

The Supreme Administrative Court

Lower Courts

Parliament

Chamber of Deputies

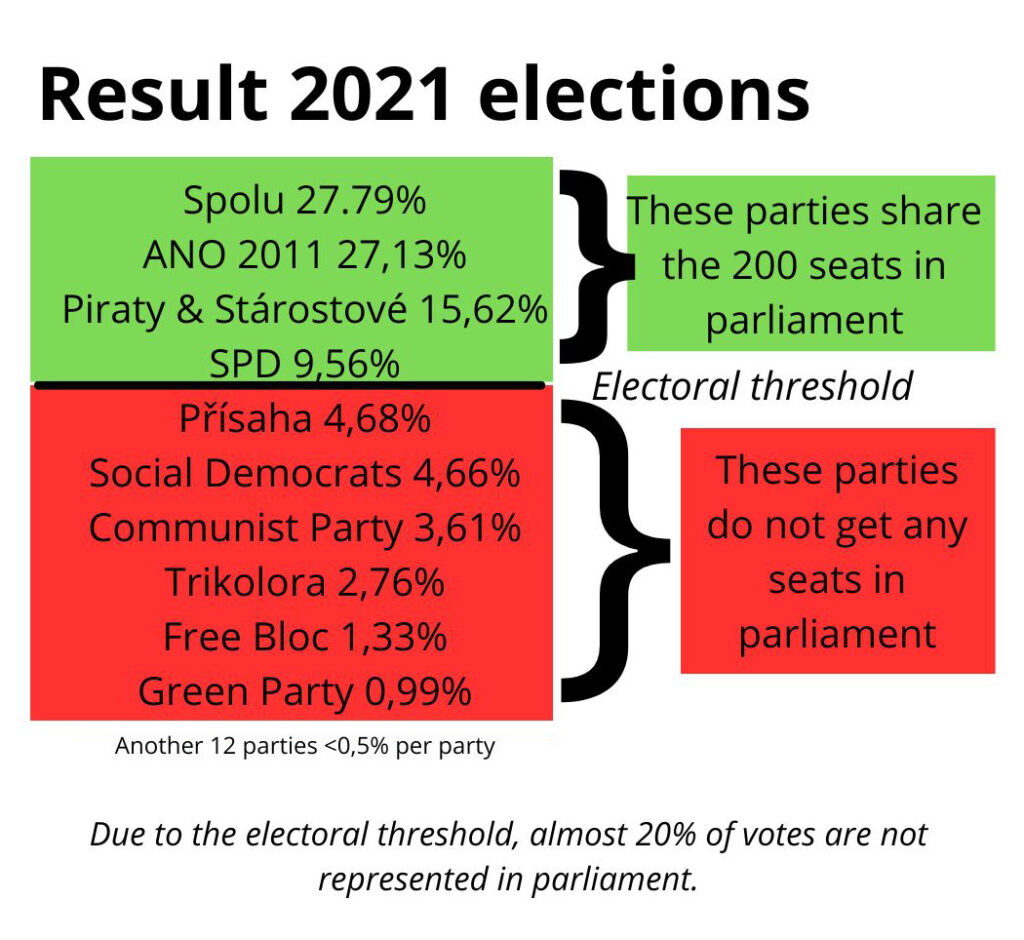

- 200 members elected for four-year terms

- proportional representation system

- at least 5% of the vote to gain seats (this threshold slightly benefits the larger parties)

- primary legislative body (passing laws, approving budgets, and ratifying treaties)

Senate composition

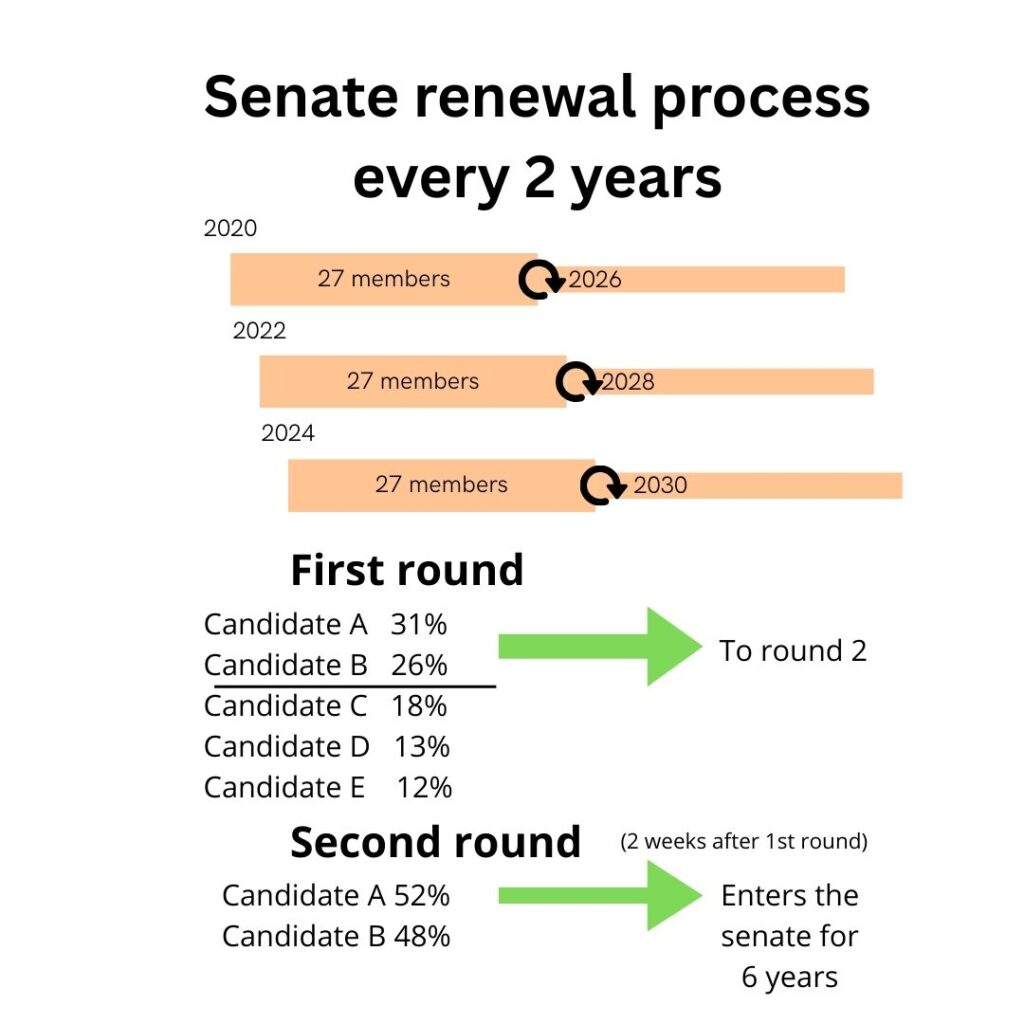

- 81 members serving six-year terms

- one-third of the seats up for election every two years (see image below)

- senators represent 81 individual constituencies

- two-round majority electoral system

- more independent (not aligned with a party) members

- less powerful than the Chamber of Deputies (some amendment powers, approval of international treaties)

- serves as a check on the Chamber of Deputies

Government

The President

- Head of State

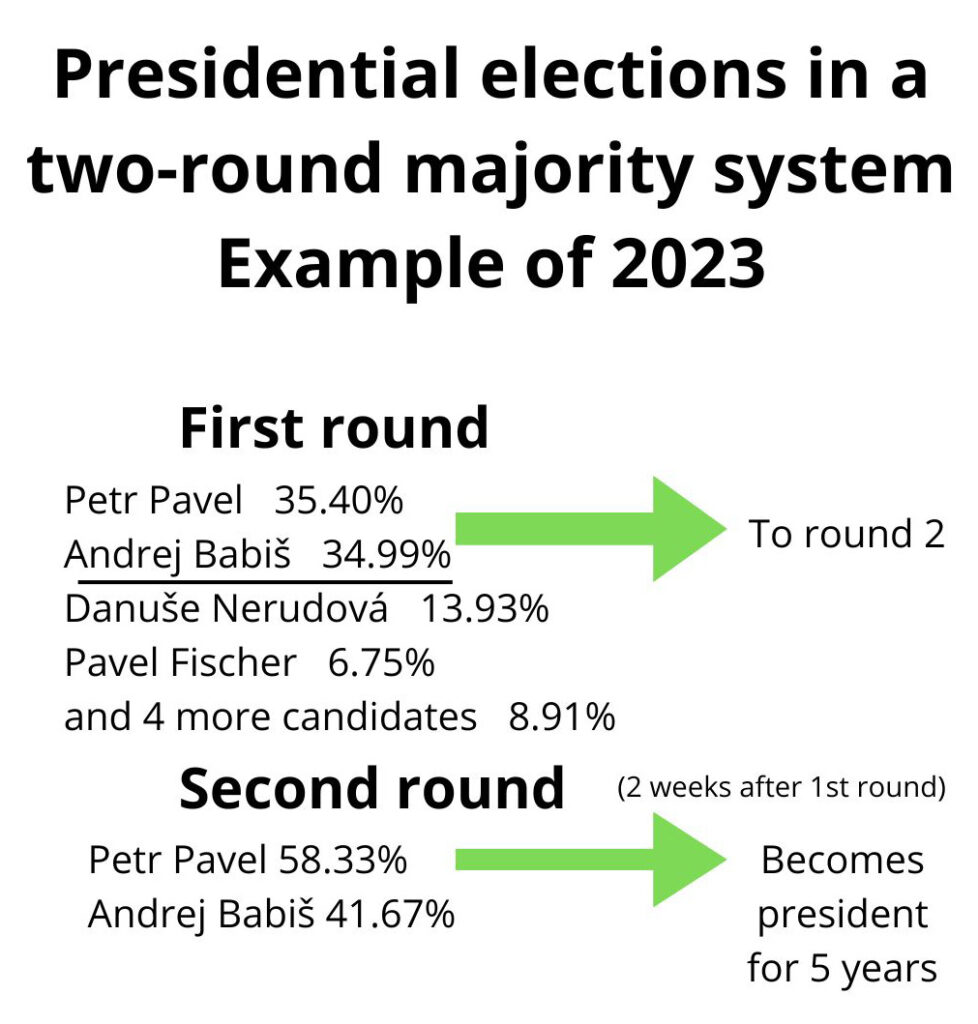

- elected in a two-round direct vote system

- elected for a five-year term with a maximum of two terms

- appoints the Prime Minister

- can veto legislation

- represents the Czech Republic internationally

- suggests and appoints key officials

The current president, elected in 2023, is Petr Pavel.

The Prime Minister

- Head of the Cabinet

- manages governmental operations and the administration’s overall direction

- possesses significant authority (proposing legislation, directing the budget, and coordinating the work of other governmental bodies)

- fundamental in shaping domestic and foreign policy and responding to national issues

The current Prime Minister is Petr Fiala (ODS).

How the Prime Minister forms a cabinet

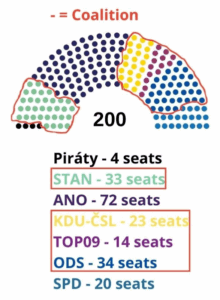

- a cabinet needs the support of at least 101 members of the Chamber of Deputies

- after Chamber of Deputies elections, the leader of the party with the most seats attempts to form a cabinet

- as no party typically wins a majority, they must negotiate with other parties to secure support for a governing program (a coalition agreement)

- if negotiations are successful, the program will pass a Chamber vote

- the President then formally appoints the Prime Minister and his proposed Cabinet members

The current government is a coalition of SPOLU and STAN. SPOLU is itself a coalition and consists of three separate political parties: ODS, TOP09 and KDU-CSL. The SPOLU-parties took part in the 2021 election as one list. Acting as one, with one leader, allowed them to beat the 2nd largest party, ANO, and get the opportunity to form a government.

The Cabinet: Parties, people and roles

The number of ministers per party, and the importance of the specific functions, is dependent on the number of seats a party has in parliament/adds to the coalition.

ODS

- Petr Fiala – Prime Minister

- Zbyněk Stanjura – Finance Minister

- Pavel Blažek – Justice Minister

- Martin Baxa – Culture Minister

- Jana Černochová – Defense Minister

- Martin Kupka – Transport Minister

KDU-ČSL

- Marian Jurečka – Work and Social Affairs Minister

- Marek Výborný – Agriculture Minister

- Petr Hladík – Environment Minister

TOP09

- Vlastimil Válek – Health Minister

- Marek Ženíšek – Science and Innovation Minister

STAN

- Vít Rakušan – Minister of Internal Affairs

- Petr Kulhánek – Minister of Local Development

- Lukáš Vlček – Minister of Industry and Trade

- Mikuláš Bek – Minister of Education, Youth and Sports

- Martin Dvořák – Minister for European Affairs

Independent

- Jan Lipavský was a member of the Piráty Party, which was part of the government until October 2024. After the Pirates left the coalition, he stayed on as an independent.

Parliament and Government: Dynamic cooperation and opposition

President and Prime Minister

A Senate Majority

The new cabinet does not always have a majority in the Senate due to its distinct electoral cycle, which produces different political dynamics. Not having a supportive Senate complicates governing, and requires broader negotiations with Senators and greater compromises on proposed laws and regulations to secure an ad-hoc majority for each individual proposal.

Multi-party Dynamics and Coalitions

The Courts

Judicial structure

The judicial branch of Czechia plays a pivotal role:

- to upholding the rule of law

- to interpret legislation

- to ensure that the actions of other branches of government comply with the country’s Constitution.

It is:

- an independent entity

- structured to guarantee fairness, impartiality, and justice.

Responsibilities:

- adjudicating disputes

- protecting individual rights

- providing checks and balances on the executive and legislative branches.

The Constitutional Court safeguards the constitutionality of laws and acts as the guardian of the Czech Constitution. It consists of 15 judges suggested and appointed by the president, with Senate approval, for 10-year terms. The Constitutional Court can annul laws or executive actions that it finds unconstitutional and protect the constitutional rights of citizens.

The Supreme and Supreme Administrative Courts are the highest in the Czech judicial hierarchy. The Supreme Court deals with civil and criminal cases. The Supreme Administrative Court focuses on administrative issues and handles disputes between citizens and the state.

Additionally, Czechia participates in the broader European legal framework, allowing its citizens to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights when domestic remedies are exhausted.

Czechia’s judiciary also includes regional and district courts, which handle cases at the local and intermediate levels. Judges are appointed for life by the President, ensuring their independence.

Challenge: Corruption

Czechia ranks 41st globally in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2023. Corruption in Czechia has remained a persistent issue, affecting politics at all levels—local, regional, and national. The misuse of public funds, bribery, and fraudulent procurement practices have been widespread, with EU subsidies frequently exploited by politicians and business elites.

The rise of oligarchic influence has complicated the political landscape, using their business empires to secure favorable policies and financial benefits while in government. High-profile corruption scandals have rocked the government, often exposing bribery, conflicts of interest, and abuse of power.

While Czechia has made some progress in addressing corruption, the lack of comprehensive public data on the number of corruption cases per year underscores the need for greater transparency and systematic reporting. Public frustration remains high, as many perceive the legal system as slow and selective in prosecuting high-level corruption, reinforcing the need for stronger institutional reforms.